This year, I began a project to attempt to read all the English translations of Homer's Odysseys. The most noticeable result has been that I find Odyssean echoes in books that otherwise have nothing to do with Homer. Without my intending it to, The Odyssey has become an interpretive lens through which I read books of all kinds. It might be a loyal, patient character who is called Penelope. Or a narrative revolving around a perilous journey to reach home. Or a theme about reconciling fate and choice. It seems Homer (and, more broadly, the ancient Greeks) is all around us.

Perhaps it’s easy to find the Odyssey in everything because the poem’s themes are archetypal. Whatever time and place humans live in, we will likely face the unknown, negotiate self with other, wrestle with questions of what is just, search for the place we belong (otherwise known as “home”). One of my favorite things about the poem (and, again, about much of the ancient Greek literature I enjoy): It doesn’t moralize as much as dramatize the questions that preoccupy us. Inevitably, a particular value system is at work, but the human struggle to enact that value system is at the center of the story. Which feels very much like life.

Isn’t that one of the reasons the poem, and the myths that populate it, has captured the imagination of so many readers and writers across millennia?

Committing to The Odyssey has led me down quite a rabbit hole of related works. The poem refers to a number of myths that I’ve been chasing down in other ancient sources. The Odyssey has also spawned seemingly endless retellings and related works. To try to read them all would be, well, impossible. Trying to has been fascinating. Also maddening. It feels like every time I turn around, I uncover a whole other mess of translations, retellings, adaptations.

I see a beautiful symmetry to the sheer volume of works that have bloomed around The Odyssey. The stories within the poem are most likely the work not of a singular genius but of a community that told and retold then over hundreds of years. When written language was invented, the poem was pinned to the page as it existed at that moment. The written version may be quite unlike the one listeners heard performed generations earlier. And the written version we read may be quite different from the one that was first written down. One way or another, literature is always being rewritten.

An intriguing contemporary example of this has been the Harry Potter series. We have the seven original books, which readers have called the “canon,” and we have acres of fan fiction, eight film adaptations, J. K. Rowling’s additions via companion books, the Pottermore website, and her Twitter page, the Cursed Child on page and stage. And we have board games, theme parks, walking tours, and a permanent monument at London’s King’s Cross Station. I’m sure I’m forgetting several somethings.

It’s astonishing, really. Especially when we consider that all this happened in fewer than 20 years. As compared with The Odyssey’s 20+ centuries.

The Oresteia is not about Odysseus, but it features Agamemnon, who makes an appearance in The Odyssey from beyond the funeral pyre (when Odysseus travels to Hades). The first play in the trilogy, “Agamemnon,” tells the story of his failed homecoming (“nostos”): His wife, Clytemnestra, and her lover murder him in revenge for Agamemnon sacrificing his and Clytemnestra’s daughter Iphigenia (in exchange for a favorable wind with which to travel to Troy). In “Libation Bearers,” the second play, Agamemnon’s son, Orestes, murders his mother in revenge. The third play, “Eumenides,” involves Orestes’ trial at Athens and revolves around questions about what constitutes justice. Is it possible to get off the rage train, or what?

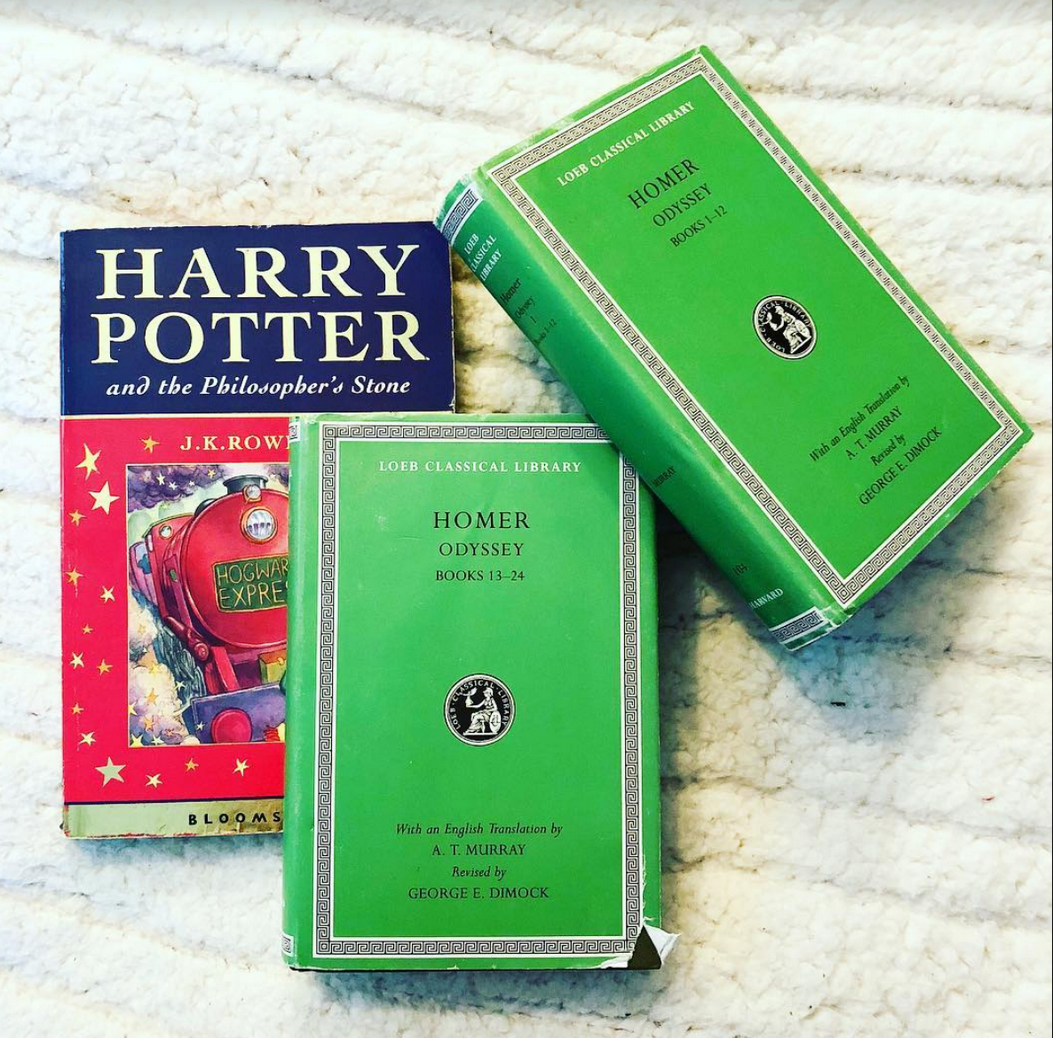

Watching Jean’s video and reading The Oresteia—along with (so far this year) five translations of The Odyssey, two children’s adaptations, four contemporary novels about women in Homer (Waiting for Odysseus, the Penelopiad, Circe, and The Silence of the Girls), and scholarship on reception literature—has made me see how deeply the intersections run between The Odyssey (and ancient Greek literature more broadly) and the Harry Potter series.

Feasts, heroes and their flaws, hospitality (“xenia” in ancient Greek) and suppliants, homecoming narratives, justice, fate and choice, and, yes, mythical monsters and characters—they’re all central to both Homer and Harry Potter. Some of the similarities are probably intentional. Some may be coincidental. But what has most fascinated me since I began this series is that the differences are as compelling as the similarities are striking.

A version of the post originally appeared on SallyAllenBooks.com.