You may have noticed that Greek mythology is having a bit of a moment lately, with several acclaimed novelists producing fiction inspired by or in conversation with ancient literature.

I’m not trying to pressure you, but I can’t help but notice how enriching it has been to read these works having also read the classical sources with which they are in conversation. It has helped deepen my understanding of the themes in both the classical and contemporary works. It has provoked me to think about the tension between human nature, which is constant and immutable, and social structures, which can change dramatically. It has led to fascinating conversations and shared insights with other readers.

In the event that you have added any of these works to your to-be-read list or perhaps have read them already but are not sure which specific classical works they reference, read on for 10 classical and contemporary pairings.

The Winter Sister by Megan Collins

Ancient sources to read: The Homeric Hymns, specifically the first Hymn to Demeter, translated by Jules Cashford

Collins—shout out to a Connecticut author—celebrated the release of her debut novel earlier this week. It tells the story of Sylvie, who returns to her hometown 16 years after her sister Persephone’s murder to care for her ailing mother and begins investigating what happened on that fateful night, with shocking results.

As you may have divined from the use of the name Persephone, the novel includes allusions to the myth of Demeter and Persephone. I won’t divulge exactly how (spoilers), but taking the time to read the first Hymn to Demeter in The Homeric Hymns will deepen the meaning of what is a somewhat pivotal reference later in the novel.

Black Leopard Red Wolf by Marlon James

Ancient source to read: The Oresteia by Aeschylus, translated by Sarah Ruden

James’ fantasy novel, which also came out this week and which (full disclosure) I have not yet read, follows Tracker, who has been tasked with locating a missing boy. Referred to as an “African Game of Thrones,” the novel is said to draw on African history and mythology.

So how does this relate to Greek mythology? In an interview with Vanity Fair, James said he tends to re-read ancient Greek drama before starting new works. “The other thing I like about reading those plays,” he adds, “is that I still think the ancient Greeks are the only people who really understood human nature.” Picture me nodding. I recommend pairing this novel with The Oresteia because it is one James specifically mentions.

Also: Ancient Greek tragedies were performed in trilogies over the course of a day. The Oresteia is the only complete trilogy to survive from antiquity, which allows readers/listeners/viewers a rare glimpse at how a trilogy’s narrative arc might unfold across a day’s performance. (Each tragedian interpreted the concept of a trilogy in his own way. While The Oresteia portrays related events in chronological order, we can’t assume this is representative.) The first play, Agamemnon, features Agamemnon returning home from Troy and being immediately murdered by his wife, Clytemnestra, and her lover. The second play, Libation Bearers, involves Agamemnon’s children planning the revenge murder of their mother and her lover, which is then carried out by his son, Orestes. The third play, Eumenides, finds Orestes seeking refuge from the Erinyes (often known by their Roman name, the Furies) whose job it is to torment anyone guilty of kin murder. Orestes eventually flees to Athens, where Athena presides over his jury trial, Apollo defends him, and the Erinyes get very fussed indeed.

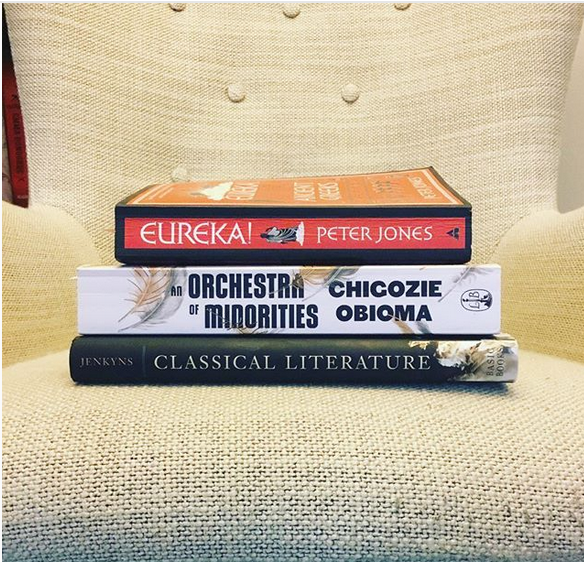

An Orchestra of Minorities by Chigozie Obioma

Ancient source to read: The Odyssey by Homer, translated by E. V. Rieu

Released in January, Obioma’s novel revolves around Chinonso, a poultry farmer who falls in love with Ndali, a chief’s daughter. Chinonso will do anything to gain her family’s approval, with devastating results. The jacket copy describes this novel as “a contemporary twist of Homer's Odyssey” within an Igbo literary tradition.

What I found enthralling about this novel were the enchanting prose and the deep dive into Igbo tradition. At the same time, I feel compelled to add that the narrative devastated me, with The Odyssey playing counterpoint. I recommend the Rieu translation in particular—though there are many each with different virtues and vices—because of its accessibility.

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker

Ancient sources to read: Trojan Women by Euripides, translated by Emily Wilson and The Iliad, translated by Stephen Mitchell

Barker’s novel came out last summer and reimagines The Iliad from the point of view of Briseis, a queen who becomes a slave to Achilles after he and his troops sack her city and kill her husband and brothers.

While I appreciate a wide assortment of reimaginings and adaptations, I am extremely finicky about retellings set in the ancient Greek world. Modern viewpoints inserted to serve contemporary agendas tend to pull me out of the novel. I recommend this novel because it feels like the ancient world. This means it will likely be upsetting to modern sensibilities. But I’m dubious that we can learn anything of value from or about the past, or about ourselves, if we remake the past so that it is palatable to who we are in our own moment.

With this novel, I recommend reading Euripides’ tragedy, which is quite an empathetic portrayal of the women of Troy who became enslaved, like Briseis before them, to the men who sack their city and murder their husbands, fathers, and brothers. And of course, reading The Iliad will also deepen the experience of Barker’s novel as much of her plot revolves around events in Homer. Mitchell’s translation is sublime—far and away my favorite among those I’ve read.

Ancient sources to read: Jason and the Argonauts by Apollonius of Rhodes, translated by Aaron Poochigian and The Odyssey by Homer

Also released last year, Miller’s novel presents as an autobiography of Circe, the sorceress who makes cameo appearances in quite a few ancient Greek myths. It has garnered raves from readers. The sense of anachronism in her narrative arc and tendency to idealize Circe at times made it difficult for me to engage, but if you don’t have my issues with retellings set in antiquity, this will likely be an enjoyable read. Miller writes lovely prose.

The two ancient texts I recommend pairing with Miller’s novel are Jason and the Argonauts and The Odyssey, two adventure epics where Circe plays important roles. I highly recommend Poochigian’s lyrical translation. It is spectacular. If you prefer a verse Odyssey, I’d suggest either Anthony Verity’s or Emily Wilson’s. I love Verity’s for the way it includes the Homeric epithets while Wilson’s is the most enjoyable I’ve read from a purely poetic standpoint.

Home Fire by Kamila Shamsie

Ancient source to read: Antigone by Sophocles, translated by Frank Nisetich

Shamsie’s novel came out in 2017 and won the Women’s Prize for Fiction. It reimagines Antigone’s central plot among members of a Pakistani-British community in modern-day London. I won’t say much more since the characters and plot closely parallel Sophocles’, though the way events play out diverges in a shocking ending.

I recommend Home Fire for the thought-provoking way it takes an ancient conflict that is rooted in extremism and refusal to engage and shows its resonance in modern times. It is a good example of how antiquity can hold up a fun house mirror to human nature—even when we’re stretched or scrunched seemingly out of shape, the essence is still there. We are still recognizable Familiarity with Sophocles’ tragedy will make Home Fire especially interesting to think about and discuss.

The Lost Books of the Odyssey by Zachary Mason

Ancient source to read: The Odyssey by Homer

The Odyssey is so often billed as a great adventure story that first-time readers can be surprised to discover Odysseus’ adventures only comprise four of the epic poem’s 24 books. And—critically in relation to Mason’s book—Odysseus himself, not the poet/narrator, tells the story of those adventures. They are rendered in the translations as his speech, which raises the question, how much of what he is telling actually happened on his 10-year journey home from Troy?

Mason plays on this in a beguiling way, presenting alternative and revised episodes and fragments. Reading this alongside Homer, especially books nine through 12 (when Odysseus narrates his adventures) is a delight.

The House of Names by Colm Toibin

Ancient source to read: The Oresteia by Aeschylus, translated by Sarah Ruden, and Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides, translated by Philip Vellacott

I’m a bit chagrined that I’ve not yet read this as it has been on my bookshelf since it came out. I suppose I’ve been nervous to dive in both because I’ve heard it is emotionally draining (fair warning) and because it is set in the ancient world. As I mention above, I can find novels set in antiquity more difficult to engage with. From what I understand, it covers the events of The Oresteia (see above) while also alluding to the precipitating event: Agamemnon sacrificing his and Clytemnestra’s daughter Iphigenia in order to receive favorable winds for the Achaeans to sail to Troy.

Though Aeschylus predates Euripides historically, Euripides’ play provides helpful background for modern-day readers of The Oresteia and, I suspect, House of Names. Iphigenia in Aulis follows the events leading up to her being sacrificed, in an emotionally gut-wrenching way that informs Agamemnon, the first play in the trilogy.

Memorial: An Excavation of the Iliad by Alice Oswald

Ancient source to read: The Iliad by Homer

This is an extended poem in which Oswald provides an epitaph of sorts for the 200 plus deaths that occur in The Iliad. It is intense, evoking the mood of Homer in a compacted form, unsurprising given Oswald worked closely with the original Greek. I felt transported by this poem and highly recommend it alongside Mitchell’s Iliad.

The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood

Ancient source to read: The Odyssey by Homer

Comedy is thin on the ground—nonexistent, really—in the above works, so let us end on a lighter note … if you can call a novella in which 12 hanged slave women serve as the Greek chorus “light.” All I can tell you is that Atwood’s wry, humorous prose had me laughing out loud often, and I was astounded at how many references she crammed into a brief novella.

The Penelopiad is narrated by Penelope 2,000 or so years into her afterlife. She gives her version of her life story, including her experiences with Odysseus, while the 12 slave women who are hung at the end of The Odysseycomment on her version of events. Atwood did her homework, which makes reading this alongside The Odysseyeminently thought-provoking. What especially makes it work for me is the underworld setting two millennia on.

Have you read any of these classical or contemporary works? If not, have I convinced you to give the classical sources a try?