By Geoffrey Morris

*This story appeared in Ridgefield Magazine.

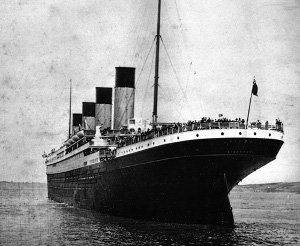

In the 100 years since the RMS Titanic sank into the chilly North Atlantic, much has been made of the chivalry of millionaires Astor, Straus, and Guggenheim—gentlemen who bowed aside as women and children were loaded onto lifeboats. But there was another man on that ship in April 1912 who deserves to have his story told as well—a man who gave up numerous opportunities to board a life raft in order to stay behind and calm those whose lives were doomed. His name was Father Byles, and he was my great-uncle.

Thomas Roussel Byles was born in England in 1870. The son of a Congregational minister, Roussel, as he liked to be called, studied at Oxford, where he converted to Catholicism before proceeding to Rome to study for the priesthood. His younger brother, William—my grandfather—also converted but moved to America to run a rubber business. There, he fell in love with Katherine Russell of Brooklyn, and when the couple planned to marry, William asked his brother to perform the ceremony. Father Byles bought a second-class, $26 ticket on the Titanic for the occasion.

After boarding in Southampton, Father Byles wrote a letter on RMS Titanic stationery to his housekeeper. The letter, dated April 10, 1912, was mailed from Ireland, where the ship stopped to take on steerage passengers. “Everything so far has gone very well,” he wrote, “except that I have somehow managed to lose my umbrella.” He described the ship, its size, and the smoothness of the ride.

Though my great-uncle’s cabin was considerably less opulent than those of the upper rung, a second-class ticket still afforded a lavish, oak-paneled dining room and wonderful views as the largest man-made object on earth sliced through pond-calm waters. “When you look down at the water from the top deck,” he wrote, “it is like looking from the roof of a very high building.”

Survivors were picked up by the Carpathia and brought to St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York City. My grandparents went there in search of Roussel, but when my grandfather heard that 1,500 people had gone down with the ship, he knew his selfless brother was among them.

In the days afterward, William learned the details of his brother’s sacrifice from survivors’ stories. As the situation became desperate, Father Byles unlocked doors to steerage and guided third-class passengers to the boat decks. Others recalled him leading recitals of the rosary. Still others claimed to have seen a priest hearing confession.

As my great-uncle helped passengers onto lifeboats, a seaman recalled asking the priest three times to board and being refused each time. Rowing away, the seaman heard the priest’s steady voice: “Our Father, who art in heaven ...”

My grandparents found another priest to officiate their wedding, as it was considered bad luck to postpone the ceremony. Later that day, they held a memorial Mass. A year later, my Aunt Mary was born and went on to become an outspoken Catholic nun. After Mary, three more daughters arrived—one of them my mother, Joan Byles Morris, who passed away in 2003.

The four sisters and their parents traveled to England so my grandmother could meet husband William’s family and they could meet her. They visited Rome for a private audience with the Pope, who declared Father Byles a martyr for the church.Through Father Byles, even the doomed found hope.